Bringing Multi-Column B-Trees to Columnar Storage

How we built compound scalar indices for Lance to optimize specific multi-predicate query patterns. A contribution story about tradeoffs, benchmarks, and when compound indices beat dual-index intersection—and when they don't.

If you’ve used Lance for multi-predicate queries, you’ve hit this wall: it only supports single-column scalar indices.

-- This query pattern is everywhere

SELECT * FROM edges

WHERE src_id = 'node_123' AND label = 'OWNS'Your options aren’t great. You can index one column and post-filter the rest (slow). You can create multiple single-column indices and intersect their row IDs (complex and I/O heavy). Or you can accept full scans.

We needed a better answer for our use case. So we built compound scalar indices for Lance—multi-column B-trees that let you index (tenant_id, status, timestamp) as a single structure. They’re not universally faster than dual-index intersection (spoiler: sometimes intersection wins), but for wide range scans and simpler query plans, they’ve been worth it.

This post walks through the problem, our design decisions, and what we learned building this. We’ve submitted PR #5480 to upstream this contribution, and you can try it on our fork.

Background: How Lance Indexing Works Today

Lance organizes data into fragments—immutable chunks of rows stored in a columnar format optimized for ML workloads. Each fragment can have its own indices, and the query engine uses these indices to prune which fragments and rows need to be scanned.

For scalar (non-vector) data, Lance provides B-tree indices. These work well for single-column predicates:

-- Single-column index on tenant_id works great here

SELECT * FROM entities WHERE tenant_id = 'acme'The index maps values to row IDs, and the query engine can skip fragments entirely when their value ranges don’t overlap with the query.

But there’s an explicit limitation. If you look at Lance’s index creation code, you’ll find this:

if self.columns.len() != 1 {

return Err(Error::Index {

message: "Only support building index on 1 column at the moment".to_string(),

location: location!(),

});

}This isn’t a bug—it’s an acknowledged gap. The Lance project has prioritized vector indices and distributed indexing, and multi-column scalar indices weren’t on the roadmap for core use cases.

The Problem with Current Workarounds

When you need to filter on multiple columns, you have two options today:

Option 1: Post-filtering. Index the most selective column, use it to get candidate rows, then filter the rest in memory. This works, but you’re fetching rows you’ll throw away. For a query like src_id = X AND label = Y where src_id matches 100K rows and only 50 have the right label, you’re doing 2000x more I/O than necessary.

Option 2: Row ID intersection. Create separate indices on each column, query them independently, and intersect the resulting row ID sets. This is theoretically efficient—you only fetch rows that match all predicates. In practice, it’s complex to implement correctly, requires multiple index lookups with their own I/O costs, and the intersection logic adds overhead.

We tried the intersection approach. It worked, but the performance characteristics were poor—row ID intersection turned sequential I/O patterns into random access. Our benchmarks showed ~200x slowdown (0.07ms/1K rows sequential → 14ms/1K rows random), making it unsuitable for production workloads.

The Design Space

Before writing code, we surveyed how other systems handle this problem.

Traditional Databases

PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQLite all support multi-column B-tree indices with “leftmost prefix” semantics. If you have an index on (a, b, c), you can efficiently query:

WHERE a = 1WHERE a = 1 AND b = 2WHERE a = 1 AND b = 2 AND c = 3WHERE a = 1 AND b = 2 AND c > 3(range on rightmost)

But not:

WHERE b = 2(skips the first column)WHERE a = 1 AND c = 3(gap in the middle)

This is the classic B-tree constraint: the tree is sorted by the compound key, so you can only efficiently seek on prefixes.

Analytical Systems

Parquet, Delta Lake, and Iceberg take a different approach. They store per-column statistics (min/max/null count) for each row group or file, then use these statistics to prune at read time. This works for any column combination—you don’t need to follow prefix rules.

The tradeoff: pruning granularity. Column statistics can tell you “this file might contain matching rows,” but they can’t give you row-level precision. You still scan entire row groups.

Key Encoding: The RocksDB Insight

RocksDB (and MyRocks) use “memcomparable” key encoding—a way of transforming typed values into byte sequences that sort correctly with simple byte comparison. This is powerful because it means:

- Compound keys can be compared with

memcmp—no field-by-field comparison needed - SIMD-friendly byte comparison is roughly 3x faster than typed comparison

- The encoding handles all the edge cases (nulls, negative numbers, variable-length strings)

This pointed us toward Arrow’s Row Format, which provides exactly this capability for Arrow-typed data.

Our Implementation

We built CompoundBTreeIndex—a new index type that extends Lance’s scalar index infrastructure to support multi-column keys. Here’s how it works.

Arrow Row Format for Key Comparison

The key insight is using Arrow’s Row Format for memcomparable encoding. Arrow Row Format converts typed column data into byte sequences that:

- Sort correctly when compared with

memcmp - Handle nulls with configurable ordering (we use NULLS FIRST to match Lance’s existing behavior)

- Support all Arrow primitive types, strings, binary, and temporal types

The comparison code is elegant:

impl Ord for CompoundKey {

fn cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> Ordering {

// That's it. Byte comparison handles everything.

self.row.as_ref().cmp(other.row.as_ref())

}

}Under the hood, Arrow Row Format handles the complexity: sign-flipping for signed integers, length-prefixing for strings, null sentinels, and all the edge cases that make “just concatenate the bytes” fail.

Per-Column Statistics for Flexible Pruning

Unlike traditional B-tree indices that only store composite bounds, we store per-column statistics for each page:

Page Lookup Schema:

min_col0, max_col0, null_count_col0,

min_col1, max_col1, null_count_col1,

...

min_colN, max_colN, null_count_colN,

page_idxThis enables pruning even for queries that don’t follow the leftmost prefix rule. Consider an index on (tenant_id, status, timestamp):

-- Full prefix: most efficient

WHERE tenant_id = 'acme' AND status = 'active' AND timestamp > '2024-01-01'

-- Partial prefix: still good

WHERE tenant_id = 'acme' AND status = 'active'

-- Gap query: per-column stats still help!

WHERE tenant_id = 'acme' AND timestamp > '2024-01-01'For the gap query, we can’t use B-tree traversal (there’s a gap in the prefix), but we can still prune pages where tenant_id doesn’t match or timestamp is entirely outside the range. This is better than full scan, even if not as efficient as a proper prefix query.

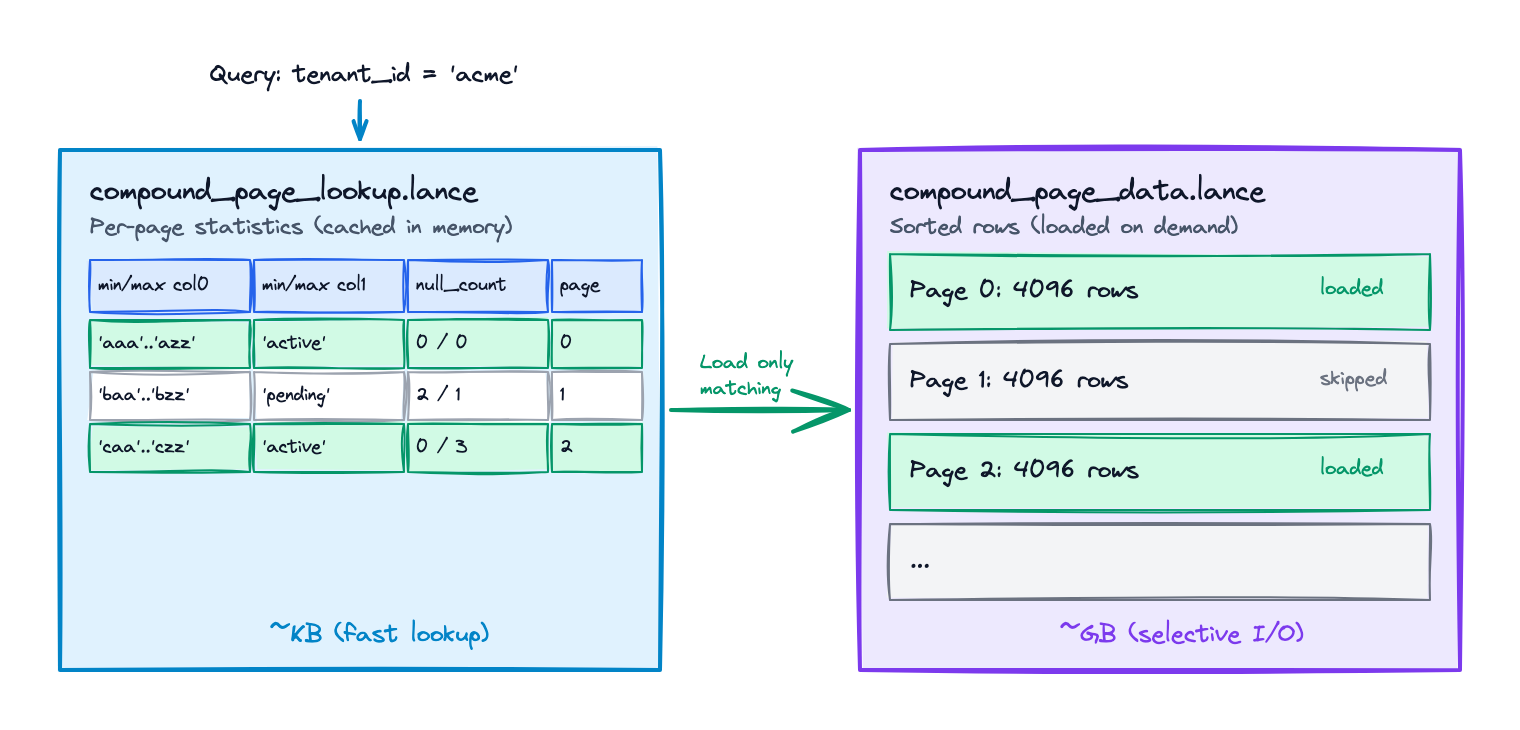

Storage Architecture

We followed Lance’s existing two-file pattern:

compound_page_data.lance: Contains the actual indexed rows, sorted by compound key. Schema is [col0, col1, ..., colN, _rowid]. Each page (default 4096 rows) is a contiguous, sorted range of compound keys.

compound_page_lookup.lance: Contains per-page statistics for query planning. This file is small enough to cache in memory, enabling fast pruning without I/O.

Query Flow

When a query arrives:

- Parse predicates: Extract equality and range predicates for indexed columns

- Prune pages: Use per-column statistics to eliminate pages that can’t contain matches

- Load candidate pages: Fetch only the pages that passed pruning (parallel I/O)

- Search within pages: Use binary search on compound keys for prefix queries, linear scan with filtering for gap queries

- Return row IDs: Matched rows are returned as a

RowAddrTreeMapfor downstream processing

For IN lists, we expand to the Cartesian product. tenant_id IN ('a', 'b') AND status = 'x' becomes two lookups: ('a', 'x') and ('b', 'x'), with results unioned. This keeps the index lookup simple while handling the common pattern of multi-value filters.

Design Constraints

We made several deliberate constraints:

Maximum 8 columns (soft limit, configurable). In practice, compound indices rarely need more than 3-4 columns. More columns mean larger keys and larger page metadata, with diminishing selectivity returns.

NULLS FIRST ordering. This matches Lance’s existing single-column index behavior and Arrow’s default Row Format ordering. Consistency matters more than flexibility here.

No nested types. List, Struct, Map, and Union types aren’t supported—Arrow Row Format works with flat column types. This is the same constraint Lance’s existing scalar indices have.

Left-prefix semantics for traversal, per-column stats for pruning. We get the best of both worlds: efficient B-tree semantics for well-ordered queries, with graceful degradation for queries that don’t match the index order.

Results and When to Use Compound Indices

Performance Characteristics

Compound indices are not a silver bullet. The benchmarks tell a nuanced story.

We ran benchmarks on multi-tenant time-series data with queries like WHERE tenant_id = X AND timestamp > Y, comparing four approaches: no index, single-column BTree on tenant_id, dual BTrees (one per column with intersection), and compound index.

Multi-fragment dataset (realistic production scenario):

| Scenario | No Index | BTree (tenant) | Dual BTree | Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenant only | 8.55ms | 2.85ms | 2.70ms | 2.92ms |

| Tenant + narrow range | 8.23ms | 2.08ms | 472µs | 693µs |

| Tenant + medium range | 7.43ms | 2.31ms | 2.77ms | 2.07ms |

| Tenant + wide range | 7.69ms | 1.89ms | 767µs | 818µs |

The key insight: dual BTree intersection often wins for narrow, selective queries (1.5x faster in our narrow range test). Lance’s query engine is good at combining index results.

But compound indices shine in specific scenarios:

- Wide range scans: When the second predicate matches many rows, intersection overhead grows. Compound indices maintain consistent performance.

- Simpler query plans: One index lookup vs. two lookups + intersection. Easier to reason about, fewer failure modes.

- Simpler storage management: One index structure instead of two, though compound indices store more data per entry.

When to Use Compound Indices

Good candidates:

- Multi-tenant data with range scans:

(tenant_id, timestamp)where you often scan wide time ranges per tenant - Graph edge tables:

(src_id, label)patterns where label cardinality is low and you’re often fetching all edges of a type - Queries where intersection is expensive: When both columns have moderate selectivity, intersection can be slower than a single compound lookup

Use dual single-column indices instead when:

- Narrow, selective queries: If your second predicate typically matches less than 1% of rows, dual BTrees with intersection will likely be faster

- Flexible query patterns: Single-column indices work for any combination of predicates; compound indices only help queries matching the prefix

- Storage is constrained: Two small indices may use less space than one compound index

Poor candidates for either approach:

- Single-column queries: If you mostly query one column, a single-column index is simpler and equally effective

- Low-selectivity first columns: An index on

(boolean_flag, high_cardinality_id)won’t help—you can’t prune effectively on the first column - No consistent query pattern: If your queries don’t share a common prefix pattern, the leftmost-prefix rule works against you

Column Ordering Matters

The most selective, most-frequently-filtered column should come first. For (tenant_id, status, timestamp):

tenant_id = X AND status = Y→ two-column prefix, efficienttenant_id = X AND timestamp > T→ prefix + gap, uses per-column statsstatus = Y→ no prefix, minimal pruning benefit

If your workload mostly filters on status, consider (status, tenant_id, timestamp) instead.

Upstream Status

We’ve submitted PR #5480 to upstream this contribution to Lance. The implementation follows Lance’s existing patterns:

- Same two-file storage architecture

- Same training/update/remap lifecycle

- Same plugin system for index registration

- Compatible with Lance’s distributed indexing infrastructure

You can try compound indices on our fork or follow the PR for upstream progress. The API is straightforward:

// Create a compound index on (tenant_id, status)

dataset.create_index(

&["tenant_id", "status"],

IndexType::Scalar,

&ScalarIndexParams::default(),

).await?;

// Queries automatically use the compound index

let results = dataset.scan()

.filter("tenant_id = 'acme' AND status = 'active'")

.execute().await?;Future Work

The current implementation covers the core use case—efficient multi-predicate lookups with prefix semantics. There’s room to extend:

- Skip scan: For low-cardinality gaps (e.g.,

tenant_id = X AND timestamp > Twhenstatushas 10 values), we could enumerate and skip through distinct values. PostgreSQL 14+ does this. - Bloom filters: For high-cardinality equality checks, per-column bloom filters could improve pruning without storing full statistics.

- Histogram statistics: Better selectivity estimation for query planning.

These are natural extensions of the per-column statistics architecture we’ve built.

Conclusion

What did we learn building this? Arrow Row Format is underappreciated—the ability to encode typed data into memcomparable bytes is a superpower for index structures, and it’s already in your Arrow dependency. Per-column statistics turn out to be the right abstraction for columnar formats, matching how Parquet, Iceberg, and Delta Lake handle predicate pushdown. And the boring approach often wins: we considered Adaptive Radix Trees and space-filling curves, but a well-implemented B-tree with good statistics covers 95% of use cases.

If you’re building on Lance and hitting the multi-predicate query wall, give compound indices a try. We think they’ll save you the trouble we went through.

Have questions about the implementation or want to discuss indexing strategies? Find us on GitHub or get in touch.